How do we know we have a pricing problem in transport?

Consider this scenario and think if it is familiar. Every day, customers request a quote from your commercial department. Pricing analysts and the commercial manager have a lot of experience in the market. They calculate the cost of all components: driver costs, paperwork, suppliers, toll, cleaning etc. Then they add the acceptable margin. In the end the commercial manager adjusts the price based on decades of experience and knowledge of the clients. That’s the price sent to the customer.

As you begin every day by looking at the increasing volumes of requests, you are happy, because revenues are up over last month, when the revenues were up compared to the previous month. Customers are happy to pay the quoted price based on your cost estimates. You are close or beyond full capacity now. You have no pricing problem, because customers are happy to pay. Good times.

Then some time in four months regular financial reporting shows that along with higher revenues margins are actually down. You (or the CEO at this point) request a full investigation and it turns out that the costs have creeped up and the pricing was off. By a lot. 15% or 20%. Prices are raised, tender contracts are renegotiated and new charges applied. Customers are unhappy because of the large increase, but they accept it and wonder why didn’t your company quote more appropriately?

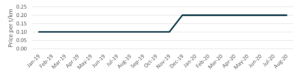

If you recognize this pattern, you are not alone. Most transport companies price on the basis of cost + margin approach. This is a simple shortcut, which allows companies to make acceptable margins and customers to have predictable prices. But the approach is problematic when demand (or supply) in the market shifts considerably. In the described theoretical (not too far from the Covid-19 situation) case, volumes begin to increase first because of stronger demand, but companies do not increase prices until their costs begin to rise (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1: In this theoretical case, demand and volumes begin to increase in May, but the company raises prices in November.

Figure 2: Volumes begin to increase earlier.

Ideally, transport companies should increase prices in-line with the demand (of course this applies to spot prices and only part of tender prices that are due to renewal). Failing to do so results in a number of negative consequences:

- Loss of a gross margin potential of 4-6%

- Volatile demands on capacity and resulting rapidly increasing costs or loss of suppliers

- Weakening competitive power over the long-term

Loss of gross margin

Increasing the prices early in-line with the demand picking up translates into higher margins simply because in an increasing demand environment raising prices does not result in lower acceptance rate. This requires of course measured, gradual increases and constant assessment of the feedback from customers.

A gradual price increase helps manage the customer expectations and avoid big unexpected surprises. According to a 2020 study by McKinsey, “a pricing transformation typically yields a revenue increase of 2-4% and thus an operating profit increase by 30-60%”. In our assessment these numbers vary depending on how volatile the markets are. In a stable environment, pricing intelligence can help add 2% of revenues as profits.

However, the market environment was not stable for long even before Covid-19. In a typical year, capacity utilization in Europe can be down or up by as much as 5% (Figure 3). Better pricing in the periods of such swings translates into margin improvements of over 6% (of revenues), which means doubling the margins for some companies.

Figure 3: Change in capacity utilization compared to the average, Euro Area, Source: FRED, ClearD3 calculations

Demands on capacity

In a period of shifting demands, pricing acts as a balancer. Failing to increase (or cut) prices timely results in rapidly increasing volumes close to or beyond maximum capacity in strong markets and rapidly drying up volumes in the periods of weaker demand. This volatility puts pressure on your costs, management complexity (including the supply chains) and people.

Managing capacity by pricing correctly is a whole separate topic covered in this article.

Weak competitive power

By far the worst negative consequence of failed pricing is the weak competitive power over the long term. A common expression we hear from transport companies is: “we are not greedy; we are fine so long as we earn our margins”. Such a dedication to customers is commendable, except in the longer term it may result in massive loss of competitive power.

If the demand justifies double the current price, there will be competitors who will charge the right price. From the same asset base such competition will earn greater cash profits and accumulated cash over time. After a while, when it’s time to renew the asset base, these competitors will be able to outbid for assets and suppliers.

Complete redesign of pricing is not necessary

Applying demand-driven intelligence to your pricing process does not require a wholesale change in systems and approaches. Demand-adjustment can already be applied to the existing pricing structure as a multiplier. Of course, there are multiple complexities to consider:

- what external data can be used to estimate changes in demand?

- what would be the sensitivity of acceptance rates to price changes?

- how are tender offers priced compared to spot transactions?

- how to assess if the pricing approach actually adds value?

These and other questions are handled in other articles in the Insights section. Alternatively, you can read through ClearD3’s approach to solving these issues.

Complementary forecasts for the end markets of freight transportation & logistics companies in Europe

to add value in making pricing and capacity decisions at your company.